I remember back in the day (or do people still do these?) when teachers in 4th or 5th grade tended to assign “the state” or “the country” report. Way too often the assumption was made that the students pretty much knew how to do these. The teacher would pass out the “packet” that explained the project, showed an example of a bibliography and often included templates for specific information that was to be included (state name, population, area in square miles, draw a map labeled with specific information and so on). Photos, usually from cut up National Geographic Magazines or brochures from travel agents were required. Typically the report was due in a month or six weeks. Each week they would have students check in with their progress and to allow students to ask questions about anything they didn’t understand about the report.

Like science fair projects it often appeared like someone a bit older (and maybe with a college degree?) might have “helped” somewhat … or they were incomplete or were of poor quality. Some did well, but how much learning actually occurred was questionable. This was the way this had always been done, it was “challenging” and, like the infamous science fair project, expected.

One of my main concerns about these projects was the assumption that students knew how to do all the work that went into the report and this was just a chance for them to put together a big project integrating all those skills. AND, after all, they were allowed to ask questions about what they didn’t understand (like they would even know exactly what they didn’t understand or know how to do). Since these were really long term homework projects the teacher didn’t see the work being done which made facilitating difficult.

Early in my career I had the same experience when facilitating projects in my classroom. I knew doing projects was supposed to be “good stuff,” so it was important to do them. Things would often hum right along as students worked on a project and I would allow myself to get sucked into observing from across the room, just to keep an eye on things, and would even do a quick task like lunch count or attendance or a quick email. Questions would pop up or a student or 2 would need some redirection, but often it was great to just let students work – or so I told myself.

Too often though after a “way too short” a period of time, some students would start claiming they were “done” or “done with that part”. Their work was almost always poor or incomplete or was off subject or all the above. This led to frustration on my part and a decreasing interest in the project by students (which was more frustrating since this is an awesome project dammit!!!).

Another observation I noted was that students were often very poor at working in a group. Even though I’d make groups have a meeting before they could get to work to go over what needed to be done that day and split up the work … which everyone in the group had to agree on so the group couldn’t just dump certain tasks on certain individuals. There would still be individual students off task, wandering around and too often causing issues. When the group would complain the student would often claim the work was dumb or boring … the group would respond that they agreed to do that part and weren’t getting anything done.

It took me awhile to understand that what was really going on (at least most of the time) was that this off track student didn’t really understand what to do, or how to do it, or even what the reason for it was. Anger, name calling and frustration was often the result (and more frustration for me … “the students were so excited about this project!!!”)

What I learned from these experiences and various classes, PD sessions and conversations with peers was that I was assuming students knew how to do these things … and mostly even the “on-task” students didn’t have a good grasp of them.

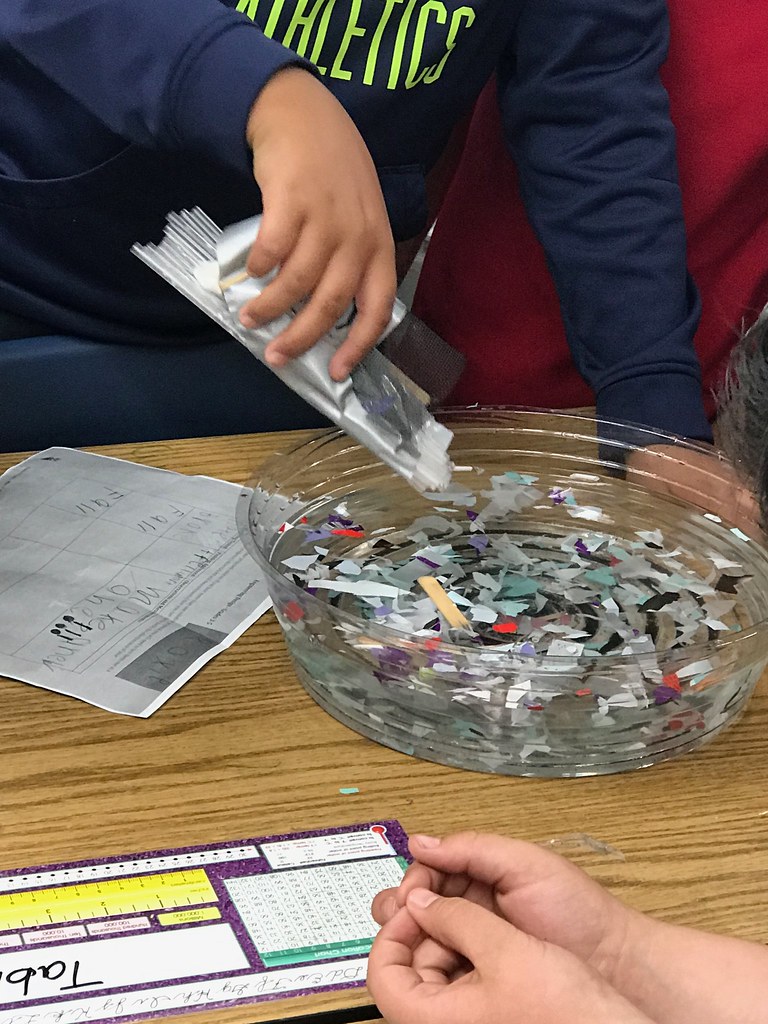

I learned to do some relatively simple individual and group projects, early in the year especially. I’d do some without much work on group dynamics and let problems arise so we could talk about the real feelings they were having and then give them some skills to constructively deal with them.

I learned to do some relatively simple individual and group projects, early in the year especially. I’d do some without much work on group dynamics and let problems arise so we could talk about the real feelings they were having and then give them some skills to constructively deal with them.

One they loved was role playing the very issues they had just experienced. I would usually take a seat in a group and demonstrate how calling each other names was probably NOT going to lead to cooperation. Instead I would teach them to ask questions like, “Toni do you understand how to do that?” – Often that was the crux of the problem … the group mate just didn’t know exactly what to do but didn’t want to admit that and look dumb. Another important skill was just noting that maybe 2 students in the group should work on that part together … which led to students experiencing really being included.

We would brainstorm how to talk to each other respectfully. Next we would role play different “off task” situations and have every group talk through the issue to a positive conclusion (how to deal with a student in their group wandering around or throwing things or just sitting there). These were a hoot, lots of laughter, especially when a student that had a reputation of being a “model student” took on the “off task” student role. It was so obvious the more we did these lessons that one of the issues was that students just didn’t have the words or skills to deal with conflicts that arise.

I also had a rule that I would not come to answer a question unless everyone in the group had the same question and had their hands up. This promoted using your group members as resources and saved lots of time. You don’t end up or bouncing around the room or with the line of students waiting to ask you a question they could have had answered quickly by the group. It also fostered a “working together” culture.

We’d talk about how fast the time goes by when you are truly cooperating and looking out for each other. And they saw this play out.

In addition I started walking around the room and sticking my head into each group to listen and watch – all the time … I’d take notes about lessons or “mini-lessons” I should consider when I’d note anything from paragraphing, a science concept, how to use a technology piece or tool, how to add white glue to paint so it doesn’t crack when you paint landscapes and other cooperative group dynamics issues and more.

I stopped making these projects homework, unless a student or students asked if they could work on it after school or at home. It was way too valuable to do assessment through their doing. Observing and facilitating student work gets to individual and class strengths and weaknesses and students see that this is something they didn’t know how to do, but has value in their learning and doing. What I made homework was resource gathering – materials, but also experts in their lives – someone’s family member that had a certain skill or knowledge to share. Some even found experts online and we had numerous video-conferences with experts contacted by students.

When I work with teachers in my current job and bring up these ideas the number one obstacle for them is not believing they have the time or “permission” to spend on building a culture of learning.

This blog is entitled, “Learning Is Messy,” and building a supportive classroom culture is as messy as it gets. But in my experience it is what this testing, accountability and assessment culture has gotten us away from.

So as you start this year off, think of doing some simple projects to build a learning culture on.

Learning is messy!